CHAPTER III

My new guide was a wispy young man. He kept his narrow shoulders thrust back in rigid posture and hands fixed in his trouser pockets. His face was a handsome carving, as if God had taken care to use a particularly sharp tool when knocking his features free from the earth’s clay. Nevertheless, he was tall and appeared healthy, in spite of his arctic complexion, no doubt a symptom of living at such an altitude here at Shackleburg. He reached down at last to take up the other handle on my trunk and carried it with me down a side corridor away from the Clock Tower’s main hall.

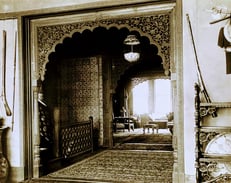

I should not have been surprised to find a fellow such as Jasper aiding me. He appeared calm, admirable, and comfortable in this place so foreign to my eyes and to my soul. These were halls and rooms he likely had trod over and over in his time, familiar and homey to he while I examined every dark corner or creak in the floor for threats and critters. But the interconnected passageways leading us from the Clock Tower to what must be dormitories housed no noticeable ghouls. The place was swept clean, its glass windows dazzling and bright, and its construction sturdy, with hardly a wisp of chilly air or speck of dust to suggest this was the oldest thing on campus, as Yvonne had stated.

I wondered—when must this have been built? Even the oldest universities of the east were founded no earlier than 1800, with a few exceptions. And here we were on a mountainside in the great state of Colorado, ensconced in a locale of higher learning, as though it had always been here, just as the mountain had.

But I teased myself. The mountain had not always been here. Not surely. I was no fool. One thousand years ago, one million years ago, this peak might have been a bump in a desert of dunes, or even beneath the ocean.

“Have you attended the university long?” I asked Jasper after we passed up to the second floor, lungs strained to a slightly noticeable degree.

“This will be my—fifth year at Shackleburg,” Jasper said with a pause for deliberation.

“Is that long? What is your area of study?”

“Long enough to be too old to die young. Here we are,” he announced. We’d arrived at door 216. “I grew up a ward to small fortune that I expanded in my younger years with some property purchases. Land, plantations, vital stretches of railroad. Their value was predictable enough that I could send myself here for an education and it’s proven far more enjoyable than overseeing accounts and figures printed on paper. Places I’d never been and never would.” He offered me the open door and I entered the quaint dormitory room. “They’re as real as I required them to be. By comparison, Shackleburg, in all the years I’ve spent here—still almost does not feel real.”

“Why so, do you imagine?”

“Because it defies me, K.K. Because it defies understanding. The mathematics of it all are fuzzy. I do my main studies down in the building called the Orrery. Professor Rakosi runs the department. I’ve heard tell that he calls the Orrery the most haunted building on campus. Imagine that. Ghosts running around our stargazing tools. Heavenly bodies leave nothing to chance. They’re as predictable as the tides. Their study simply requires observation and devotion, and yet, I—well, what business has a ghost with stars of the night sky?”

“What does Professor Rakosi say when you ask him such a question?”

“I wouldn’t know. I’ve never met the man, personally.” We stepped out of what would become my room and into the corridor. I made a quick attempt to count the doors on the dormitory floor, but my thoughts were interrupted when Jasper carried on speaking. “I hope you didn’t come to this place imagining you’d study at the feet of the Five Old men each and every day?”

He raised a taste from his snuff while I contemplated the question. “I’m sorry?”

“The Five Old Men. The Tenured professorial chairs don’t teach their classes personally. You’ve come to study ontology? Professor Loomis? You’ll never see him.”

“You sound certain. You said—what was it—five years and you’ve never encountered this Professor Rakosi?”

“Do you reckon my reasoning when I suggest that this place defies me, K.K.?” Jasper asked with a mirthless chuckle. He threw his arm over my shoulder and his smiling teeth shone. We made for the stairs as he squeezed my neck. “What’re we made of? Don’t you wonder? What’re we made of that makes them—their minds so big, and bright, and wise—that they don’t look us in the eye, electing to lecture from an unseen lectern? Their absence puzzles me each day I raise my head to the sun. And yet raise it, I do. This is what my life has become.”

“We’re yet young. You’ll only grow wiser,” I said. “Wiser than they, maybe, who won’t come and commiserate directly with the student body.”

“Ah,” Jasper hugged my neck tighter before releasing it at last. “You and I are fast friends, K.K. But, no. I don’t believe I am wiser than the Five Old Men. Not yet.”

“Not yet.”

We kept up spontaneous conversation on our return walk to the Clock Tower’s common room. It was a blessing to behold the other men my age, of freshness and clarity that went unfound in Platavilla nearly all my life. I contemplated Jasper’s assertions toward the Five Old Men, my alleged teachers. Defiance of my father’s wishes had ferried me down unknown roads to souls similar to mine. Now another challenge confronted me on the road—more defiance. Were these Tenured professors as wise in the ways of learning as I supposed, and as Jasper supposed? Were they deserving of his discontent? Their station loomed far above his, a young man, hardly more than a boy, as I was, and he flapped his flippant gums in their general direction as recompense for yearslong neglect of his developing brain. Was Jasper suffering a malady? Or simply a lesson he could not fully touch as he was?

When might we in life know where to set our strength, our wit, and our insistent demands against an order of the world and tear down the crumbling plaster pantomiming some false acropolis? Dear reader, what does time teach that cannot be more quickly learned, if your mind is sharp enough, and your heart is clear? Yet youth still enjoys the tread of a boot upon his neck, somehow certain, that a lesson dwells in this leather imprint.

“Did Jasper sequester you in the usual broom closet?” one boy about my age asked as I joined the gathering around the fire.

“I’d sleep under a bench if it meant an opportunity to be in a place as this,” I answered, smiling at the quickness of my words. “It was a rich and hearty journey to make it to Shackleburg and nearly cannot contain myself at the thought. To be away from those old confines and be here among such fine gentlemen.”

“We’re not fine,” the other boy laughed. Jasper settled into an empty chair and did not remark. “Absolutely aren’t gentlemen, either. Tell me, K.K., did you truly faint in your carriage ride from the railroad like some startled waif?”

“Yes. Who told you that?”

“The witch at the infirmary,” the boy said. “When your trunk was sent ahead.”

“She’s not a witch, Ianto,” a third boy said.

“Why is she obsessed with touching skin, Monroe?” the boy named Ianto asked.

“She’s studying to be a physic. A doctor,” Monroe said.

“Women cannot be physicians. It is simply not possible, just as I cannot force a child out of my own belly. Women can only be women. Women can only be witches.” Ianto pointed to me. “What did the witch do to you?”

“She was kind to me,” I said.

“Did she touch you?” Ianto asked. “Did she touch your skin?”

I thought for a moment. “No. She—didn’t. I don’t think she did, now that I remember.”

“That witch touched you, I’d wager,” Ianto said.

“Has a woman ever touched you, Ianto?” Jasper asked then. “No. No, I apologize. I selected the wrong words. I ought to have said—Ianto, no woman has, nor ever shall, touch you. Not in sickness, health, living, or death.”

The other boys had started laughing before Jasper had completed his insult. Ianto could do nothing but retreat into his body, into his chair, away from the reversal of accusations. His face looked as if it could collapse into itself, rotten nose and all.

“I will admit, Ianto,” I said at last as the laughter dimmed, but not fully gone. “I grew up without a mother. But I did not grow up without women. And that’s all I’ll say on the topic, even among this ill-gotten company of half-gentlemen.” It was defense enough, even if my display of spine was hardly more than piling on. I’d have to mend fences with Ianto later. I didn’t need to foster animosity so soon after my arrival, but I would not shrink from barbs, either.

“Why not say more?” Ianto retaliated.

Much too desperate. “You wouldn’t understand a word I say,” I explained in a calm tone. In that moment, I believed every word, as did the other fellows.

Errant jeers subsided when Monroe refocused the conversation. “Was Yvonne indeed the one you met at the infirmary?”

“Yes,” I said, warmed at the admission. “She was kind, and generous, and witty.”

“She is,” Monroe answered.

“Monroe is sweet on her,” Jasper interjected calmly.

More jeers. “Are you?” I asked.

“I don’t understand a word you mean,” Monroe said with a smile toward Jasper. Monroe had a head shaped like a bean. He did not shrink from the conversation like Ianto did though. He was stout and brave.

“Does she know?” I asked next. I dragged out the beat to find if Monroe would drown in the silence. “That you—understand?”

“Of course not,” Monroe said. He showed no defeat, only certainty.

“Do you visit her at the infirmary?” I asked him.

“No, but we attend lectures together. We meet before and following lectures, and talk, and sometimes walk. She’s like me, she walks quickly. It’s how we always found ourselves together, away from other students as they go about the campus. It’s much too cold to dawdle like these tortoises. Yvonne always—I always see her smile, even when the evening chill is coming down. I see it in my mind and it warms me. And I don’t ever feel lonely when I walk with her.”

I nodded as plainly as I could, sharing the slightest possible expression. “I think he gets it,” I said to those gathered with us. “But, do all of you?”

“Lad’s sweet on her,” Ianto said.

“He’s in love,” Jasper corrected.

I sighed and shrugged. “Has she ever visited you here?” I asked, hoping for a quick end to the conversation, then quickly adding, “No, the women likely aren’t allowed in the men’s dormitory, are they?”

“Certainly,” Monroe said. “We hold parties in this room frequently.”

“Lord,” I laughed a little. “What about at the women’s dormitory?”

This was met with immediate silence. The fire snapped, and even it felt dulled by my question.

“We have never been,” Jasper began, paused, then continued. “The administration has not ever shared the location of the women’s dormitory. The women students will not tell us. Nobody will tell us. There are theories and rumors. The women attend all the same classes as the men. They enjoy all possible rights and privileges we do. We welcome them at every opportunity to visit and entertain in this very hall, as Monroe said. But, no, the women’s dormitory remains an absolute secret.”

-- Alex Crumb

Follow on Twitter