Ghost Little uses a specific writing technique and style. For structure, I use a derivation of Pixar's story structure, modified by Tim Rogers, an essayist and critic whom I admire.

Defining this structure was vital for me. I struggle for focus and I need to create very secure guardrails for myself. Plus, it's neat to see how you can work familiar story tropes into a structure you normally wouldn't imagine.

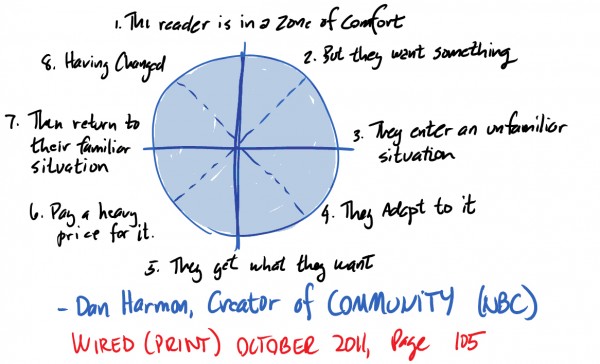

While the Pixar model informs the overall story structure, I draw from Dan Harmon's episode structure for individual chapters. Dan Harmon is a TV writer, and the creator of shows including Community and Rick & Morty. He envisions each episode like a wheel of desire. Like the Pixar structure, this simple structure provides remarkable story propulsion. It is repeatable. It fits any number of characters. It is open to interpretation.

I write long chapters. There are nondescript breaks within each chapter to compensate. The breaks usually fall during the clicks of the "wheel." You might even be able to notice them or anticipate them, if you come to know how I structure things. That's okay. It's never a sure thing. I often need to surprise myself and will stab at the process with modifiers to keep from becoming complacent.

I write from the perspective of the omniscient narrator. As the narrator, I know everything about the world. I do not know what the characters are thinking. There is never precise internal thought, or wishes, or hopes, or dread, described on the page, because it is not information I possess.

I do not know what is going to happen next, just like the reader. That's fun for everyone, right? Come along with me and we may make a discovery.

I know a character's history. We won't know how that affects the character's relationship with another character in the present until we see them in a room together though.

I use short sentences. I try to use the exact word required for the given situation. If that means the words used are short, that's okay. If the exact word required is polysyllabic, that's okay, too.

I hope to describe exactly what I see in my mind's eye to deliver what is occurring in the story. I use whatever tools necessary to do so. There are no rules about structure and formatting that can or cannot be used. I just do the job.

The characters' spoken dialog is sometimes long and rambling because that's how people usually talk in real life. Realistic characters are interesting, loving, and terrifying.

I can write on any available surface. I usually use my old laptop hooked up to a DAS mechanical keyboard. The click on those keys is luxurious. I kind of hate that old laptop though. I've also written a good deal on my phone's virtual keyboard while sitting on the bus or the train. It's dead, daydreaming time that I try to get the most out of, if possible.

I have used a lot of word processing and note-taking software including, Microsoft Word, Google Docs, Evernote, Notepad++, and TextWrangler, as well as blogging platforms like Blogger, and HubSpot, both the CMS and COS tools.

Ghost Little uses as few words as possible to tell its stories. Using few words is respectful of the reader's team. Lord knows they have a lot of other ways they could be occupying themselves. I know I could lose their attention at any moment, so I had better not waste a second of it. There are occasions when I'll think: "ah, this is a great idea, I should save it for later on in the book though." Then I realize that the story might run out of steam and I'd never have the chance to use this idea. I'll test it in the story's current state and see if it can be included. Why waste an interesting idea?

I will not, however, force an idea. For example, if it's too exciting, and I know that now is not the time for the character to be excited, I won't use it. This is the benefit of using a derivation of Pixar's universal story structure.

The Pixar universal story structure earned decent exposure over the years. If you've seen a lot of Pixar's movies, you'll be alarmed how much they all have in common, and how many different stories you can paint into those lines.

Pixar's stories go like this. It is listed as rule no. 4 in their book:

#4: Once upon a time there was ___. Every day, ___. One day ___. Because of that, ___. Because of that, ___. Until finally ___.

Simple, right? The other rules are all online and are worth seeking out. For now, let's see if we can fit a Pixar movie like Toy Story into this structure.

"Once upon a time, there was a toy cowboy named Woody. Every day, Andy, Woody's owner, would play with Woody and all his other toys. One day, Andy got a new toy, Buzz Lightyear, whom he adored even more than Woody. Because of that, Woody pushed Buzz out the window. Because of that, Woody felt regret, and had to rescue Buzz from Andy's neighbor, Syd, battling obstacles all the way. Until finally, Buzz and Woody settled their anomosity and returned home to Andy, who was happy to have them both back, best friends forever."

Now, what's tricky is figuring out how much attention to give to each segment. If you count the blank spaces, you'll find six. Those are my six chapters.

Chapter one is our cold-opening. I give most of the credit to the James Bond movies for including a cold-opening to my stories. This is the main character, fully formed, having a heck of a day.

Take the introduction to Bond in Casino Royale, for example.

"Once upon a time, there was a spy chasing a bomb-maker through Madagascar."

Wow, a lot will take place in the next few minutes for this character. We're going to learn how our protagonist behaves in a lot of different situations.

|

| The Story Structure Circle, Dan Harmon, 2011 |

This is where the Dan Harmon story structure circle kicks in, visible above. When I begin the story with a James Bond-style cold opening, the character is having a normal day, and is likely comfortable, at least for a moment. If you check item 2 on the circle above, you'll notice it reads, "But they want something." This is when the day goes sideways and gets busy. Moving on to items 3 and 4, the character has go outside their comfort zone and adapt to a new environment to get what they want.

When items 5 and 6 arrive, the character has been forced to give up a great deal to obtain this new something-something. Maybe they took it by force? Maybe they realize they went too far? On to items 7 and 8, the character has returned to their origin point, perhaps at the end of the day. They may give up what they've obtained, upon return, but above all else, they have changed, there is no mistake.

These are flexible boundaries. I try to adhere to them and often succeed. I never succeed 100% though.

Ghost Little has been developed over several platforms. Pieces have been written using Blogger, Evernote, Google docs, NotePad ++, Text Wrangler, HubSpot CMS, and many others.

Ghost Little is currently hosted on the HubSpot Website tool. Find the link to the Pixar rulebook here.